Lusatia after the Elections – Making Active Citizen Participation a Reality

10.09.2019

The recent elections in Saxony and Brandenburg have redrawn the political maps in both states. And although the process of forming new coalitions is sure to be challenging, the parties that have ruled up to now have come out relatively unscathed. Most of them are likely to remain in power.

It comes as no surprise that both top candidates declared just hours after the the exit polls emerged that they would continue to engage more directly with citizens in the new governments. In the months preceding the elections, the Governor of Saxony Michael Kretschmer practised what he preached in this regard and was rewarded for his hard work. But he appeared anything but relieved and buoyant when announcing the election victory on Sunday evening. Despite his Trojan efforts, this result was barely enough to secure the mandate to form a government.

The lines of conflict are clear for all to see in the coal-mining regions of Lower Lusatia (Brandenburg) and Upper Lusatia (Saxony), where the AfD had some of its most impressive victories. For all the attempts of the federal and state governments to take a more proactive approach to the pending structural transformation, once again 30% to 40% of the local population voted for the AfD, a party that denies climate change.

At the same time, there’s no getting around the fact that both new governments will have to intensify their climate protection efforts. In the draft Structural Renewal Act, government funding in support of structural transformation is tied to the coal phaseout. If this funding were conditional on the fulfilment of sustainability criteria – a possibility currently being debated – this would pay off in the long run and also help to avoid bad investments. Pressure to make structural transformation sustainable is only going to mount with the participation of the Greens in both state governments on the cards.

A key factor in the voting behaviour of many Lusatians and people in other rural parts of Eastern Germany is their long experience of being powerless and politically marginalised. Be it in terms of jobs, traffic planning, cultural amenities, or demographic change, it’s often been the periphery that loses out. Many perceive the planned coal phaseout as just another hardship imposed on them, where they themselves have no say in the matter. That’s why the promises of the AfD hold such allure on the eastern periphery. The party presents itself as a long-awaited counterforce, while keeping silent about its own limited capacity to alter the basic structures of these rural areas.

More than just listening: structured participation

Against this background, the assurances by both prospective governors that they will seek even closer contact with their constituents are understandable but also short-sighted. Simply giving people more attention is not going to allay their sense of powerlessness. And besides, it’s not feasible for state governments to maintain a hectic schedule of public engagements on a permanent basis. This would only undermine the established structures for effective governing in the medium term. Instead, participation can and must be structured and institutionalised at local and regional level.

There is a dire shortage of forums where diverse positions come into contact with each other. We lack democratic spaces where explicit and implicit ambivalences and conflicts can be aired and, most importantly, rendered negotiable. Political action arises in a dialogue, above all in cooperation. So rather than polemical, one-sided judgements, what’s needed is societal interaction and the creation of a Mitwelt or “common world” (Hannah Arendt (1972/2011): Vita Activa oder Vom Tätigen Leben. Munich: Piper). Only then does it become possible to appreciate one’s own position in relation to others, become acquainted with other lived realities, discuss fears, visions and concrete ideas, and reach compromises, instead of perceiving political action as a monolithic threat to one’s own way of life.

Scientists, think tanks and activists have been refining participatory approaches and formats for decades. The time has now come to put them to the test in dialogue with the actors involved.

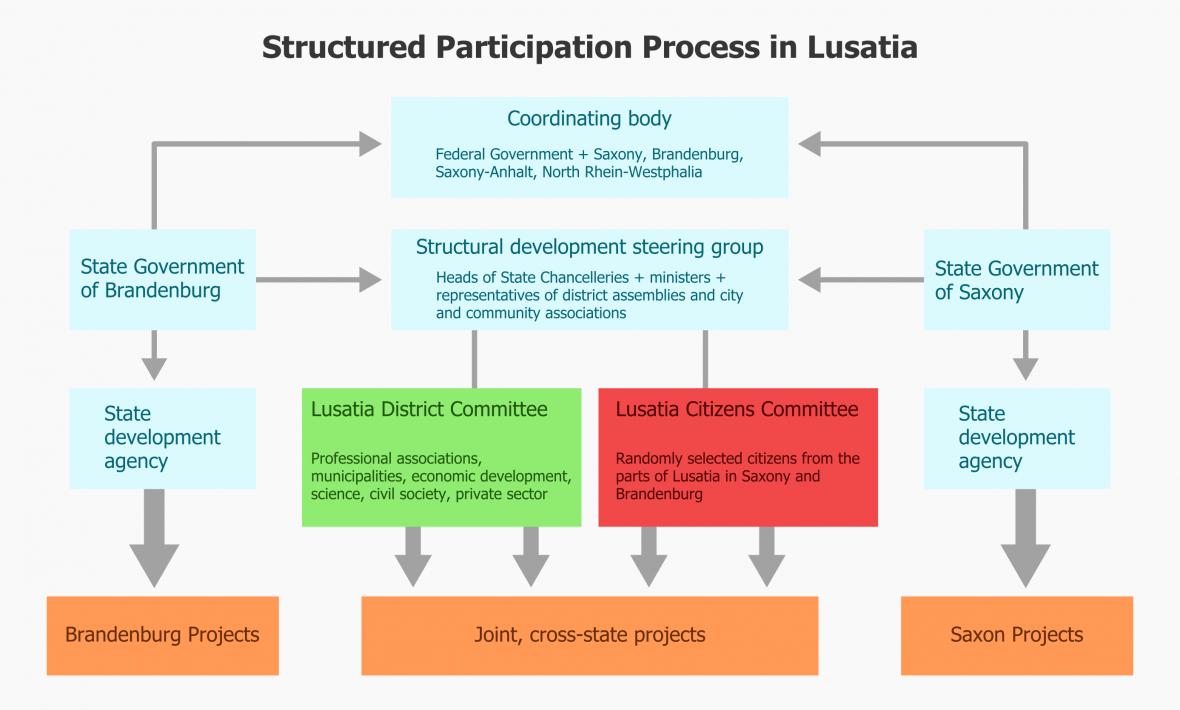

Institutional innovation in the form of a citizens committee

A citizens committee for Lusatia would supplement the bodies that have just been set up to steer the structural transformation with organised interest groups. This committee would be made up of randomly selected citizens from across Lusatia, who would have the right to make their own suggestions for the allocation of structural transformation funds. The coordination bodies at state level would then have to take these suggestions into consideration. In the best-case scenario, this continuous exchange of views would give rise to communities united by a sense of common responsibility, a development that would help to transcend the manifest and discursive divisions into pro- and anti-coal camps.

Particularly in a situation where large sections of the population are not convinced by their governments, talking and listening may be wise, but it’s not enough. Collective planning and action, i.e. institutionalised citizen participation, will break the cycle of political exclusion.

This idea presented here is a work in progress that the IASS team has brought into play in the political process connected with the structural transformation of Lusatia.