New visions to support European youth on climate chaos

30.09.2022

2018 marked the dawn of a new age of youth activism in Europe. Climate justice and the question of intergenerational justice are now taking centrestage. The slogans associated with the Fridays for Future movement capture the existential crisis of contemporary youth, triggered by the vision of “stolen futures” and the burdens they will almost certainly have to shoulder tomorrow if effective climate policies are not adopted in the present.

But along with this newfound agency, young people in Europe are also grappling with experiences of victimhood. The rise of the Fridays for Future (FFF) movement coincided with a wave of extreme weather events in Europe with deadly consequences for individuals and communities. These included wildfires and heat waves in Greece in 2018 and 2021, and in Portugal in 2017 and 2022, and severe rainstorms in Germany in 2021.

In this blog, I examine how young people in Germany perceive the climate crisis and how this is reflected in their voting. I also consider the broader implications of their predicament and various ways in which European youth could be supported.

Facilitated process on climate chaos

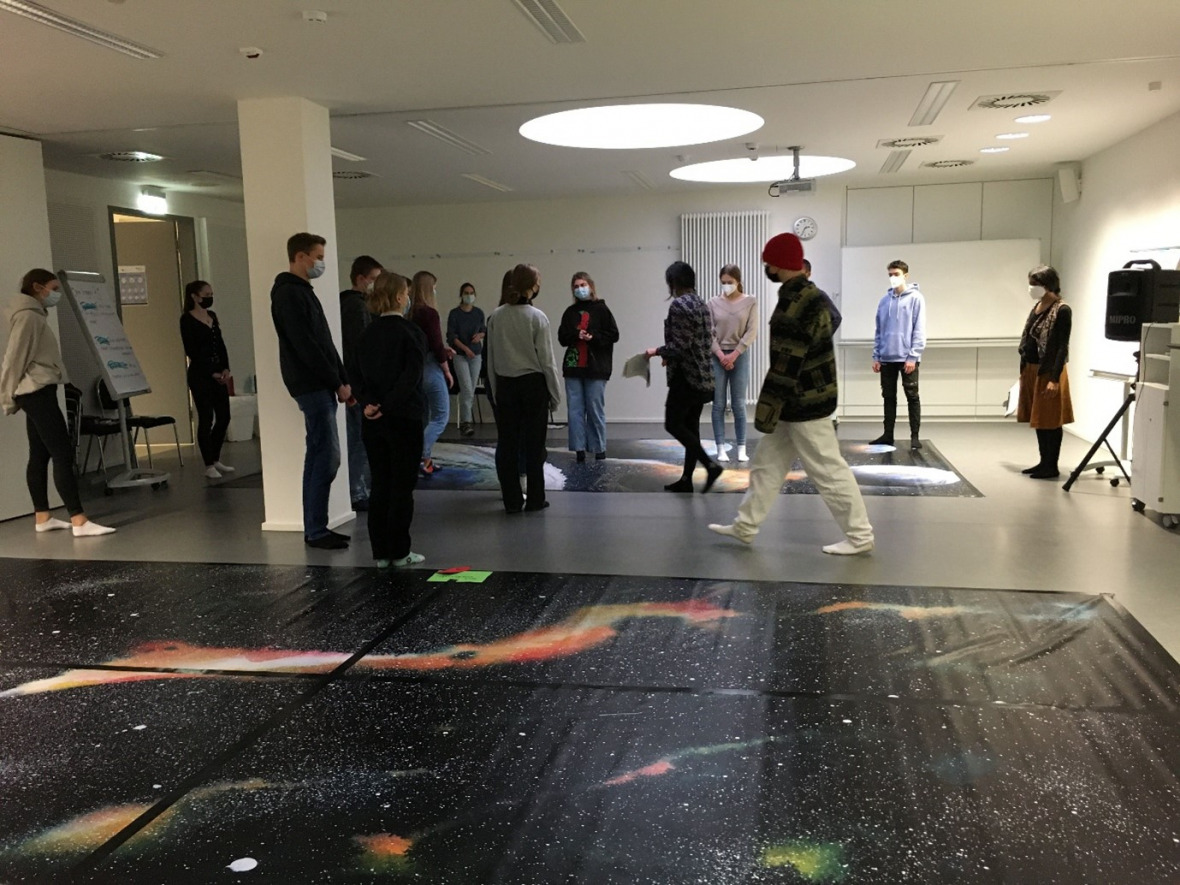

My case study are German youths (15-21 years old), and my sample spans 56 young people so far. In special workshops I have been facilitating an embodied experience about the climate crisis for young people. Titled “Climate Chaos”, the experience enables young people to explore their perceptions, thoughts, and feelings around the climate crisis. The central cornerstone of this process is a spatial map upon which participants are invited to position themselves in relation to how they perceive the climate crisis (North represents the climate crisis as an economic crisis, West as a psychological crisis, South as a cooperation crisis, and East as a spiritual crisis). The participants are instructed that there is no correct position in this exercise and that they can also take up a position outside the quadrants.

The workshop begins with an embodied experience of chaos, known as the systems game, in which participants must select two other people, without indicating who they have chosen, then move so as to maintain an equal distance between themselves and each of the two people selected as the group moves to the sound of composer John Williams’ “Duel of the Fate”. The game enables participants to become more attuned to their perceptions, chaos, and bodies immediately before they position themselves on the map. The experience also helps to mitigate the herd effect.

In a next step, participants are invited to explain why they decided to take up a particular position. After listening to each other, they are invited to re-position themselves. The aim here is not to research German youth per se – in fact, the only data collected during the session concerns the participants’ positions. Rather, it is an opportunity to explore the climate crisis together with youth in small mini workshops.

Witnesses, whether they are teachers or assistants, are invited to document their own observations and thoughts as they accompany the workshop and to consider what they learn from the participants and what they youth might need as they grapple with the climate crisis.

The four dimensions of climate change as a crisis

| Direction | Type of crisis | Rational given |

| North | Economic crisis | The crisis is caused by production and consumption patterns in the West. It is these practices which are at stake. |

| West | Psychological crisis | The crisis is mainly due to a fear response to change. The fear-response encourages some of us to avoid thinking about climate change, to emotionally distance ourselves from it , or to feel fragmented and unable to respond meaningfully. What is at stake is our relationship and response to climate chaos. |

| South | Cooperation crisis | We live on the basis of individual rights and have lost our connection to the collective rights of the common good. What is at stake is our way of relating to each other and cooperating for the common good. |

| East | Spiritual crisis | We are realising that we are the only species on Earth that does not contribute to the richness and diversity of life. We are changing the Earth’s geology and processes. What is at stake is humans' role on Earth! |

How do European youth perceive the climate crisis?

In the facilitated experiment, the majority of the young participants (80%) positioned themselves as perceiving the climate crisis as an economic-psychological crisis (NW). These youth felt that climate change is “external from themselves (so far), made by adults/others, solutions are blocked by adults/others” (Witness). Therefore, “the majority of them locate the crisis in the economic quadrant, equating an external problem with an external solution” (Witness). This quadrant was clearly favoured by boys. Especially for boys, the “technical appears as a realm with clear views and shapes, analytical; not as fuzzy as spiritual, feeling… which is still highly unpopular to talk or tap into at that age” (Witness). As one witness says, young people want a “normal life and are looking for a way to respond to the challenges.” For them, looking at the climate crisis as an economic crisis feels like the right response to their desire for a normal life. The session frequently leaves participants feeling “more confused about climate change because their education teaches them that there is one right expert opinion” (Witness)

In just one of the three sessions, five participants positioned themselves as perceiving the climate crisis as an economic-spiritual crisis (NE). All five were girls who “needed to be in a small group to dare position themselves there” (Witness). The girls expressed “sadness and the frightening open question: what would it mean to change our spiritual attitude, or rather, develop one? And how, and with what consequences? At least the girls dare to locate the problem there…” (Witness).

Four participants positioned themselves as perceiving the crisis as a psychological-cooperation crisis (SW). In each of the three workshops, those that took this position were often alone or with just another person. However, “they were sure about their position“ and “often appeared to have thought or read a lot about climate change” (Witness).

When they were invited to re-position themselves after listening to each other, the general movement was a movement from North towards the centre.

Caught in-between: Youth as heroes and victims

In the last German general election, the youth vote largely targeted the Greens (25%) and the liberal party, FDP (21%). Many young people expressed disenchantment with the major parties. This trend reflects what we witnessed and heard during the climate crisis workshop – the “certainty of the students about the fact that the ones in charge, even the ones who understand the (climate) crisis, do not act, do not ‘walk their talk’” (Witness) - hence their propensity to vote Green. At the same time, most youth want to “lead normal lives and enjoy the same opportunities as their parents” (Witness) – a fact that is perhaps reflected in their turn towards liberal parties.

When asked about their agency at the end, some youth talked about courage – “that it takes courage to be unpopular, to be truthful, to be consistent, and that it will be painful in some ways” (Witness). In general, “they want to be taken more seriously but also think that those in charge only talk but do not act although all the evidence about the climate crisis is available” (Witness). Indeed, not being take seriously is at the heart of the eco-anxiety felt by young people according to a global survey of eco-anxiety. The despair they feel is not attributed only to a bleak future, but “was associated with beliefs about inadequate governmental response and feelings of betrayal”.

Supporting European youth on climate change

Given that we, scientists, educators, and practitioners cannot immediately change government policies, how can we support European youth on climate change?

As one witness says poignantly, “they need us – adults - as supporters. We need to be there for them, give them love, understanding, hope, and direction (Orientierung). They – as one boy expressed - cannot handle all the stress by themselves. They are alert, open-minded, and asking the right questions.”. Indeed, young people were “born into an age of climate chaos, share a fear of losing their normal life and are looking for a way to respond to the challenges. They are often unaware of their many strengths and coping abilities” (Witness)

In the workshop, I asked the participants whether I should provide more scientific information on climate change to support their agency and the overwhelming response was “No, we don’t need it! We have been fed with so much scientific data” (Witness). We also talked about education and how the session challenges the idea that there is one right answer, a notion that is pervasive in education, exam culture, and expert knowledge.

Ultimately, I decided to stop running the workshops after the third session as I felt that it left the youth feeling overwhelmed as they grappled with experiences of agency and victimhood. Facing that challenge will be critical, I believe, but young people must also be brought into political participation processes that are non-hierarchical and supported by role models that stimulate reflective dialogues, learning, and co-creation – rather than only expert knowledge. As one witness shared, young people would benefit from “hierarchy-free and interdisciplinary consultation and decision-making” and “open participation processes for the political implementation of necessary changes. Bottom-up democracy”. The Youth Parliament established in Wales to work closely with the Welsh Parliament comes to mind as one good example. In my opinion, one without the other – that is participation in political processes, without exploring our inner worlds (including our dilemmas, beliefs, and emotions), or vice versa – is not the way. How we can combine both is the focus of my work as a Justice Fellow at the IASS.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to ProWissen for providing space and invitations for hosting the session with schools and to Angela Borowski for her support.